Yabuzaki-en’s Global Ambition —From Asahina, One of Japan’s Finest Gyokuro Regions (Gyokuro & Matcha)

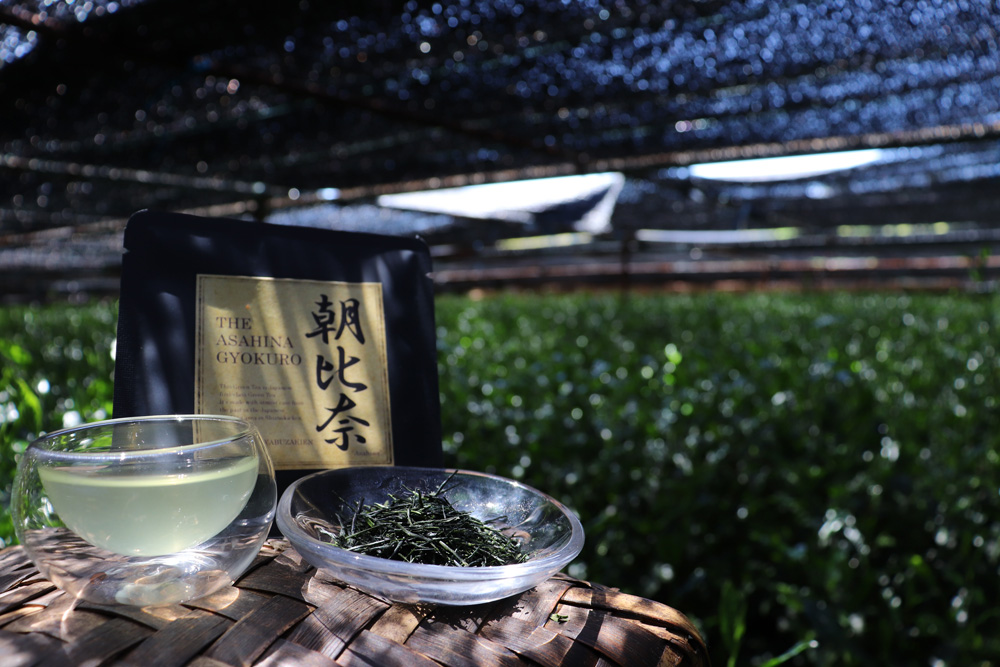

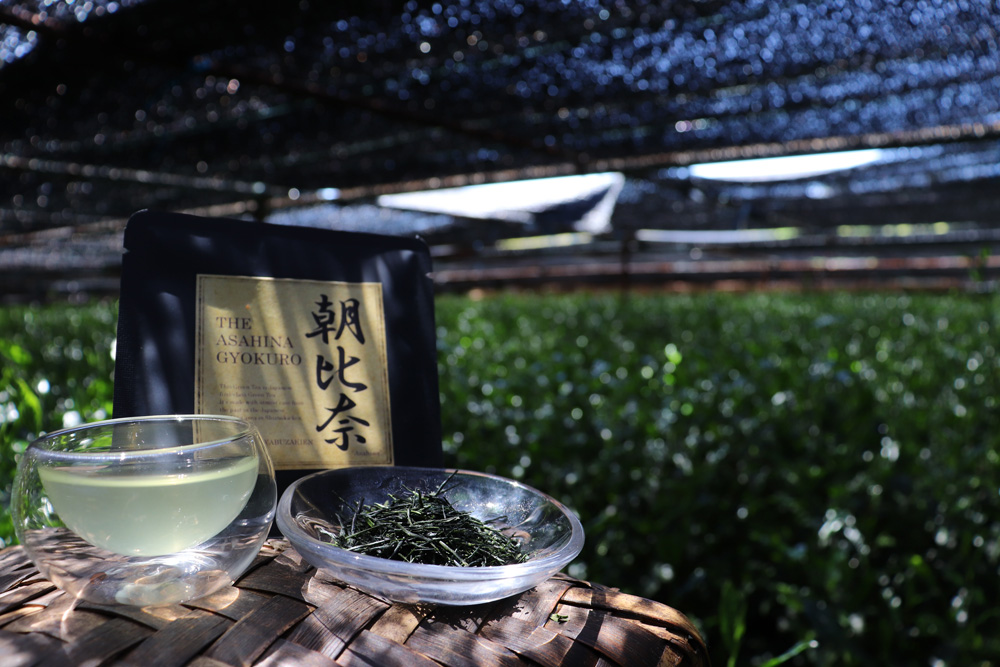

Shizuoka’s Asahina district, located in Okabe, Fujieda City, is recognised as one of Japan’s three premier gyokuro-producing regions, alongside Uji in Kyoto and Yame in Fukuoka. Gyokuro is a high-grade green tea distinguished by its cultivation method, which involves shading the tea bushes — a process known as hifuku — to block sunlight. This technique allows the leaves to develop a rich aroma and a deep, elegant umami.

The focus of this feature is Yabuzaki-en Co., Ltd., a tea producer whose origins can be traced back thirteen generations to a historic farming family established in the mid-Edo period. Today, the company manufactures premium gyokuro and matcha in the Asahina region. Yabuzaki-en became incorporated in 2000 and now operates as a modern tea-producing enterprise.

In this article, we explore not only the unique elegance of tea cultivated in Asahina, but also Yabuzaki-en’s reasons for now setting its sights on the global market. Through an interview with company president — and serving Fujieda City councillor — Masayuki Yabuzaki, we delve into the background behind this strategic shift.

Contents

- 1 About Yabuzaki-en

- 2 The Story Behind Premium Gyokuro’s Powerful Umami and Rich Aroma

- 3 Interview: Asahina Gyokuro Goes Global — Yabuzaki-en Reveals the Profound Depths of Japanese Tea

- 3.1 Flavour Shaped by Mist and Soil — What Makes Asahina’s Tea Truly Exceptional

- 3.2 Aged to Perfection: Gyokuro as Profound as Fine Wine

- 3.3 From ‘Uji-cha’ to ‘Asahina Gyokuro’: Building a Brand Rooted in Local Matcha and Gyokuro Heritage

- 3.4 Japan’s Tea Market Shrinks, but Global Interest Grows – How Yabuzaki-en Is Reaching the World

- 3.5 Shizuoka, Uji, Yame: Discover Gyokuro’s Unique Flavours Through Single-Origin Teas

- 3.6 How to Brew Gyokuro

- 4 ~Information Of Yabuzakien Inc.~

- 5 ~Gyokuro Specialty Store COMO~

About Yabuzaki-en

Yabuzaki-en is a distinguished tea merchant with a lineage that spans thirteen generations of proud tea farmers. Its origins trace back to the mid-Edo period in the Asahina area of Okabe, Shizuoka Prefecture,where the family dedicated itself to producing premium gyokuro.

In 2000, the business transitioned from its long-standing model of “growing, processing, and selling everything in-house to a new corporate structure. Today, the thirteenth-generation owner, Mr Masayuki Yabuzaki, leads the estate in preserving its heritage while upholding an unwavering commitment to quality.

▲At ‘como’, Yabuzaki-en’s speciality Asahina gyokuro shop, visitors can purchase gyokuro and a selection of other teas.

▲At ‘como’, Yabuzaki-en’s speciality Asahina gyokuro shop, visitors can purchase gyokuro and a selection of other teas.

Before reorganizing as a joint-stock company in 2000, Yabuzakien was a self-grown, self-produced, and self-selling tea farm. The Yabuzakien family has been making gyokuro since the mid-Edo period, and Masayuki Yabuzaki, the 13th generation of the family, is currently the owner of the Yabuzakien farm.

The Story Behind Premium Gyokuro’s Powerful Umami and Rich Aroma

Gyokuro is one of the most luxurious categories of Japanese tea, celebrated for its deep umami, natural sweetness, and unmistakably rich aroma. Owing to its rarity and the labour-intensive methods required to produce it, gyokuro sits at the very top of the Japanese tea price range.

At ‘san grams’, a tea café headquartered in Kikugawa, Shizuoka, visitors can enjoy gyokuro crafted by Tohei Maejima of Yabuzaki-en, served as part of their café menu.

The hallmark flavour of gyokuro is created through a cultivation method known as ‘hifuku’ (shading), in which the tea bushes are covered to block direct sunlight, reducing the amount of light reaching the leaves.

For shading, growers use materials such as kanreisha, a mesh fabric known for its excellent light-blocking and heat-retaining properties, or komo, a traditional woven-straw covering.

▲Cold gauze(Kanreisha)

▲Cold gauze(Kanreisha)

▲’Kōmo’ — a shading material woven from straw

▲’Kōmo’ — a shading material woven from straw

When sunlight is restricted, the tea leaves accumulate high levels of amino acids, particularly theanine the source of gyokuro’s umami. Ordinarily, exposure to sunlight converts theanine into tannins — the compounds responsible for bitterness and astringency.

However, by maintaining a shaded environment, theanine remains in the leaves. As a result, bitterness and astringency are suppressed, allowing the signature strong umami and gentle sweetness of gyokuro to develop.

Gyokuro is also distinguished by the care taken during harvest. Mechanical harvesting often mixes in stems and other parts of the plant, which can introduce unwanted flavours. In contrast, gyokuro is picked by hand, leaf by leaf, ensuring only the finest leaves are selected and the purity of flavour is preserved.

For sencha, it is common to harvest ‘isshin-niyo’ — a stem and the top two young leaves. Gyokuro, however, is made by selectively picking the larger, softer leaves located lower on the stem, which yield a smoother, more rounded taste.

Through careful shading and meticulous processing, gyokuro develops a unique aroma known as ’ooi-ka’, literally ‘the scent of the cover’. This fragrance is expressed the moment the tea touches the palate and lingers gently through the nose, resulting in a rich and layered aftertaste.

This ooi-ka is the very essence of gyokuro’s character. Its depth and elegance continue to captivate Japanese tea enthusiasts around the world.

Interview: Asahina Gyokuro Goes Global — Yabuzaki-en Reveals the Profound Depths of Japanese Tea

We spoke with Mr. Masayuki Yabuzaki, head of Yabuzaki-en and a serving member of the Fujieda City Council.

Flavour Shaped by Mist and Soil — What Makes Asahina’s Tea Truly Exceptional

–Could you tell us about tea cultivation in the Asahina region?

The area along the Asahina River is blessed with fertile soil, and frequent mist and haze drift through like a natural shower. This phenomenon provides gentle humidity, creating an ideal environment for growing tea.

Thanks to these favourable natural conditions, Asahina has long been recognised for its exceptional quality tea.

The region also remains relatively cool even during the warmer months from April to June, making it highly suitable for shaded cultivation. In fact, around 90% of the tea fields here are cultivated under cover, enabling farmers to consistently produce high-quality leaves.

There was a time when Yabuzaki-en would bring its freshly picked leaves to a shared local factory to process them alongside neighbouring farmers. However, when that facility closed, we took the opportunity to establish an independent approach to tea production under the Yabuzaki name.

–So the shared factories no longer exist today?

Not quite. Two cooperative factories still operate in the Asahina area: Ryusei Green and Aohane Tea Studio Takumi. Both mainly manufacture kabusecha, a type of semi-shaded tea. Beyond these, there are no large-scale tea factories, and only around five or six medium-sized farms are scattered throughout the region. We all know each other well — it’s a very friendly community!

In recent years, however, it has become increasingly difficult to make a living solely from agriculture, and the number of part-time farmers has grown. We too have begun cultivating crops other than tea.

–What kind of crops do you grow besides tea?

Our rough annual farming schedule looks something like this:

April–May: First flush (ichibancha) harvest

May: Rice planting

June: Second flush (nibancha)

July: Third flush (sanbancha)

September: Fourth flush (yonbancha)

October: Rice harvesting

October–December: Mandarins (mikan)

February–April: Bamboo shoots (takenoko)

–You also grow bamboo shoots?

Yes, Asahina’s bamboo shoots are known for their outstanding quality. They are so highly regarded that major buyers in large consumption areas purchase them in bulk, meaning they rarely reach the general market. Strangely enough, in places where excellent tea grows, delicious bamboo shoots also seem to thrive.

Aged to Perfection: Gyokuro as Profound as Fine Wine

In general, Japanese tea is said to taste its best—and fetch the highest prices—during the first-flush season in April and May. However, the fresh, green aroma that characterises first flush tea is quite different from the fragrance sought in gyokuro.

For this reason, producers do not immediately process the freshly picked aracha (unrefined tea leaves). Instead, the leaves are stored for a period to allow them to ‘rest.’

–So rather than taking advantage of that fresh first flush character straight away, you deliberately keep the leaves in storage?

Exactly. While freshness is normally prized in new tea, gyokuro is unique in that the leaves are intentionally rested and allowed to mature. As the months pass through autumn and winter, the tea gradually ‘ages’, softening the youthful green notes of the first flush. (Here, ‘ageing’ refers to the leaves developing towards the ideal matured state for gyokuro.)

Over time, this process draws out the deep, distinctive aroma that defines gyokuro, and once the leaves reach their peak condition, they are finally processed into finished tea.

The completed gyokuro is then sealed and stored using nitrogen flushing, encouraging further maturation even after finishing.

This is one of the defining characteristics of Yabuzaki-en’s gyokuro. The flavour deepens as it ages. No one can say with certainty how the taste will evolve—it is something you must ultimately discover for yourself.

That said, anyone who has worked with gyokuro for decades can usually predict its flavour to some extent, even without tasting it.

— It really does sound like vintage wine. In that case, does gyokuro also have ‘good years’?

I believe so. For instance, the 2019 harvest suffered from frost damage, so its quality may not have been the best. On the other hand, 2016 enjoyed excellent weather, producing exceptionally fine tea—gyokuro from that year is truly delicious.

–So does that mean gyokuro from a good year is more expensive?

Not necessarily. Years with stable weather often yield higher-quality tea, but because stable weather also leads to a larger harvest, supply increases—and prices can actually fall as a result.

▲Asahina Gyokuro is also sold as a premium bottled japanese tea.

▲Asahina Gyokuro is also sold as a premium bottled japanese tea.

From ‘Uji-cha’ to ‘Asahina Gyokuro’: Building a Brand Rooted in Local Matcha and Gyokuro Heritage

For many years, most of the tea leaves harvested in this region were transported to Uji in Kyoto (one of Japan’s most renowned tea-growing regions), where they were processed using Uji’s traditional methods and then distributed under the umbrella of ‘Uji tea’.

However, revisions to the regulations governing regional labelling now stipulate that the term Uji-cha (Uji tea) may only be used when the raw tea leaves are sourced exclusively from prefectures adjacent to Uji—namely Mie, Shiga, Osaka and Nara.

Following this change, we decided to discontinue marketing Asahina tea as ‘Uji-cha’. Instead, to more accurately convey the unique character of the Asahina area, we established a new brand: Asahina Gyokuro.

–So the tea nurtured here in Asahina was once regarded as being of such high quality that it qualified as Kyoto’s Uji tea?

Absolutely. Moreover, the Asahina region is also a thriving producer of matcha, and at Yabuzaki-en we are placing considerable emphasis on matcha production.

–How is matcha generally made?

Using the brick-built tencha (lightly dried, shade-grown leaves that are ground into matcha) furnace located in our tencha processing facility, we dry the raw tea leaves without kneading them, producing tencha. This tencha is then ground into a fine powder using a stone mill, becoming what we know as matcha.

With the recent global matcha boom, the number of factories producing tencha in Shizuoka Prefecture has grown to more than ten. Considering that there were only four in the past, this increase is remarkable.

Our ‘Luxurious Rich Matcha Latte’ is one of the products we proudly recommend at Yabuzaki-en. It is exceptionally well crafted, and we hope many people will have the chance to enjoy it.

Japan’s Tea Market Shrinks, but Global Interest Grows – How Yabuzaki-en Is Reaching the World

The Shizuoka tea industry today stands at what feels like a critical crossroads: decline or revival. The biggest challenge lies in the shrinking demand for loose-leaf tea, which has pushed down tea prices across the board. As a result, it has become increasingly difficult to make a living from tea alone, accelerating the shortage of successors in the industry.

With domestic demand continuing to fall, Yabuzaki-en has set its sights firmly on the global market. The reason is simple: the scale of the overseas market far exceeds that of Japan. In fact, ‘selling 0.1% globally can be larger in market volume than selling 1% within Japan.’

In preparation for exporting to Europe, the farm has also begun cultivating organic teas certified under the Japanese Organic JAS standard.

–Is there truly demand for Japanese tea abroad?

Absolutely. In fact, Yabuzaki-en regularly receives overseas enquiries through Facebook and Instagram. During the tea season, more than 100 groups of international visitors come to the farm each year.

The number of visitors grew so rapidly that we even hired additional English-speaking staff — one of the turning points that encouraged the farm to pursue global expansion in earnest.

Against this backdrop, we see tremendous potential in the use of social media. In recent years, more people have begun travelling to the farm because they ‘want to drink the tea’ or ‘want to see the tea fields’ in person. These visitors include not only individual travellers but also those arriving through travel agencies.

Many of them are influential communicators, and the way they share their experiences of Yabuzaki-en via social media has been incredibly valuable for us.

Shizuoka, Uji, Yame: Discover Gyokuro’s Unique Flavours Through Single-Origin Teas

Shizuoka—particularly Asahina—is well known as a gyokuro-producing region, alongside Kyoto’s Uji and Fukuoka’s Yame.

In Shizuoka, the cultivar Saemidori is considered a good match for gyokuro, while Uji producers often work with Ujimidori, Saehikari and Samidori. In Yame, cultivars originating from Kagoshima, such as Yutakamidori, are commonly used.

In the past, these cultivars were typically blended and offered simply as ‘gyokuro’. However, in recent years, greater attention has been given to teas that highlight individuality—such as ‘single-cultivar’ or ‘single-farm’ teas—collectively known as ‘single origin’.

As this concept gains traction, growers and tea merchants have increasingly begun presenting their teas individually.

▲The term ‘single origin’ originally came from the coffee industry, but it has now begun to take root in the world of Japanese tea as well.

▲The term ‘single origin’ originally came from the coffee industry, but it has now begun to take root in the world of Japanese tea as well.

Perhaps as a result of this shift—this is purely based on my own impression—interest in teas grown in mountainous regions, especially those offered as single origin, has been steadily rising.

–I see. Yabuzaki-en also cultivates tea in a mountainous area. What specific differences are there between teas grown in the mountains and those from the lowlands?

For example, if you compare the liquid colour, teas harvested in lowland areas often display a vivid green hue, whereas teas from mountainous regions tend towards a yellowish amber. There are also clear distinctions in aroma and flavour: once you try them side by side, the differences are unmistakable.

In any case, I encourage you to start by simply relaxing and enjoying a cup. From that first sip, you will surely begin to appreciate the profound depth and charm that tea has to offer.

In terms of how to drink it, feel free to enjoy it in any way you like. Taste and preference differ from person to person. There is no single ‘correct’ way to drink tea. I hope you will savour your tea time in the style that suits you best.

How to Brew Gyokuro

1. Warm both the teapot and teacups by pouring in hot water and letting them heat through.

2. Cool boiled water to 50–60°C, then pour it over 5g of gyokuro leaves.

3. Allow the tea to steep quietly for 1.5 to 2 minutes.

4. Pour the tea little by little so that the strength remains even, making sure to extract every last drop.

Savour the rich umami, refined sweetness, and lingering aroma that gently rises through the nose—qualities nurtured by the fertile terroir of the Asahina region, renowned for producing exceptional gyokuro.

Related articles : Gyokuro and Matcha Tasting in a Japanese garden in Gyokuro no sato【Asahina Gyokuro and Matcha, Shizuoka Prefecture】

Recommended Articles : Discover the Best Matcha Sweets at Japanese Convenience Store!

Recommended Articles : Nanaya matcha gelato: the bridge to the future of Japanese green tea【Shizuoka, Tokyo, Kyoto】

~Information Of Yabuzakien Inc.~

| Address | 1135-1 Katsurashima, Okabe-cho, Fujieda City, Shizuoka Prefecture 421-1113, Japan |

| Website | http://yabuzaki.co.jp/ You can purchase products via this online store as well. |

| Phone number | +81 54-667-3633

(japanese and english) |

| Electronic money and credit card | |

| Open hours | Ask us |

| Holidays | Please ask us |

| Parking | Available |

| Access | About 15 minutes by car from Okabe Utsutani Interchange |

~Gyokuro Specialty Store COMO~

| Address | 964-36 Utsutani, Okabe-cho, Fujieda City, Shizuoka Prefecture 421-1131, Japan |

| Website | http://yabuzaki.co.jp/

You can purchase products at COMO or on its online shop. |

| Phone number | +81 54-667-3633 |

| Electronic money and credit cards: accepted | Credit card available |

| Open hours | 9:00 to 17:00 |

| Holidays | New Year’s Day |

| Parking | Available |

| Access | About 5 minutes by car from Okabe Utsutani Interchange |

| Writer | Norikazu Iwamoto |

| Career | Ochatimes chief editer. Meeting with Vice Governor of Shizuoka prefecture. Judge of Shizuoka 100 tea’s award in 2021~25. Ocha Times link introduced at website of World O-CHA(Tea) Festival 2022, Tea Science Center, The City of Green Tea Shizuoka, Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries. |

| English translator | Calfo Joshua |

| Career | Born and raised in England, living in Japan since 2016. Studying arboriculture in Shizuoka Prefecture whilst operating his landscape business Calfo Forestry. Appreciating the nature of Japan and the culture that places such importance in it. |

Go to Japanese page

Go to Japanese page

on the red bar to close the slide.

on the red bar to close the slide. to see the

distance between the current location to the Chaya.

to see the

distance between the current location to the Chaya.